Svalbard’s permafrost—the layer of ground that stays frozen year-round—is in a uniquely vulnerable position. Despite its location high in the Arctic, it is the warmest permafrost found at such a latitude, making it especially sensitive to rising global temperatures.

Recent scientific findings show that this frozen ground is warming and thawing at a concerning pace. Since 2009, temperatures within the permafrost have been rising by as much as 0.15°C each year. This isn’t just a surface-level issue; the warming has been detected as deep as 80 meters below the ground, indicating a long-term and widespread change.

One of the most visible signs of this is the deepening of the “active layer”—the top layer of soil that thaws in summer and refreezes in winter. In western and central Spitsbergen this layer is now typically 100 – 200 cm deep. This layer is now thawing more deeply each summer, creeping further down into what was once permanently frozen ground. In some areas and for some time periods, this thaw has been measured to be advancing downwards by over 6 cm every year.

Looking ahead, computer models paint a stark picture. If high greenhouse gas emissions continue, the top several meters of permafrost in many of Svalbard’s coastal and low-lying areas are projected to thaw completely before the end of this century.

This ongoing thaw has serious real-world consequences. As the ice that once acted as a cement for soil and rock melts, it dramatically destabilises the landscape. Mountainsides become more prone to landslides, posing a direct risk to infrastructure and communities. Along the coast, the thawing ground is much weaker against the force of ocean waves, leading to rapid erosion that can cause the shoreline to crumble away. The thawing of Svalbard’s permafrost is fundamentally reshaping its environment and increasing the hazards for everything and everyone on the archipelago.

Source: Hanssen-Bauer, Inger, et al. “Climate in svalbard 2100.” A knowledge base for climate adaptation 470 (2019).

Active Layer and Permafrost Conditions in Longyearbyen 2024

The ground temperatures in Longyearbyen follow a seasonal pattern. In winter, the ground is typically colder than the air, as the surface loses heat through thermal (longwave) radiation during the polar night. In summer, the ground is usually warmer than the air, as it absorbs solar (shortwave) radiation.

During winter 2023/24, the surface was covered with snow from beginning of November until the end of April. During the summer, precipitation usually falls as rain.

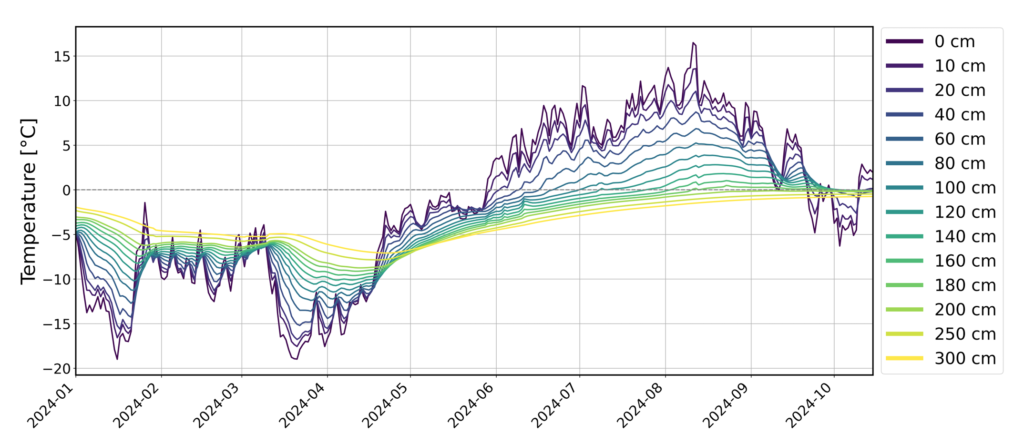

The mean soil temperatures from all boreholes from January to October 2024, measured at depths of 0-3 m, shows a seasonal cycle. Soil closer to the surface (blue and purple lines) responds more quickly to weather conditions and therefore shows greater temperature variations. In deeper layers (yellow and green lines), the temperature changes gradually over months because it takes time for heat to penetrate deeper into the soil.

From January to April, the upper layers are generally colder than the deeper layers as the soil is cooled from the surface. From mid-April, temperatures near the surface become warmer than the deeper layers, driven by solar radiation and rising air temperatures. By the end of May, surface temperatures rise above 0°C and the soil at the surface thaws.

Active Layer Formation 2024

Permafrost is soil that has been frozen continuously for at least two years. The layer of soil near the surface that thaws and refreezes each year is called the active layer. The active layer is critical for factors such as soil stability, ecological processes and water movement in the soil.

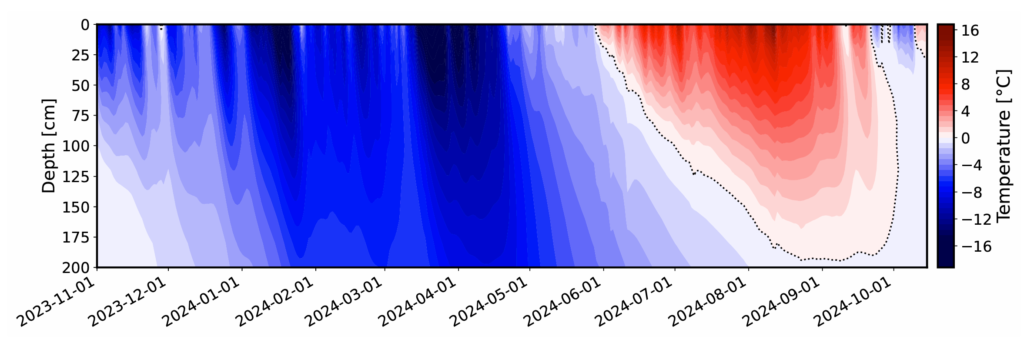

In November 2023, the soil was cooled from the surface downwards. At a depth of 2 metres, the soil temperature reached its minimum in mid-January 2024.

In late winter and early spring, the surface layers began to warm due to rising air temperatures and increased solar radiation. This warming caused the soil temperature to rise above 0°C, marking the formation of the active layer. The thaw depth deepened until mid-August 2024, when it reached its maximum depth of 2 metres.

The thawed layer remained unfrozen until about mid-September 2024, when refreezing started from the top and thereafter extended to deeper layers.